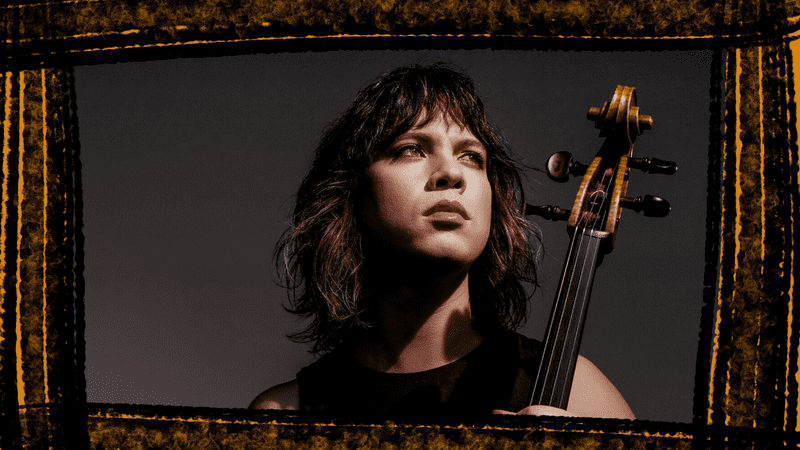

Artist Propulsion Lab - S1 E8 - Halfie: A Memoir by Andrew Yee

Release Date: October 27, 2022

kʻou inoa

Breath

koʻu inoa

Andrew Yee: koʻu inoa is by my great friend Leilehua Lanzilotti.

It just sort of hypnotizes you and what ko’u inoa means in native Hawaiian is “my name is.”

My name is Andrew Yee, my pronouns are she/they, for now.

I'm a cellist. I play cello in a string quartet called the Attacca Quartet, but I also play on my own.

I'm also a composer, and a parent.

kʻou inoa continues

John Schaefer: This is an audio memoir by cellist and composer, Andrew Yee. They’ve been exploring their identity through a recital series called Halfie. And this memoir draws from their Halfie recital in the Greene Space, as well as music and conversations with people important to them. I’m John Schaefer, and this is the Artist Propulsion Lab.

Ko’u inoa continues

In Manus Tuas - Dad's Family

Andrew Yee: My dad's side of the family, which is my Chinese side, came over to the United States, during the cultural revolution in China. Because of the cultural revolution and who they were, they had to get papers of another family. So my original family name was Chin, but my grandparents got papers with the last name Yee.

My grandfather came over first. I called him Yeye. And he opened a small laundry in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He earned enough money to get my grandmother and my father, who was a small child, over to the United States. They had tickets to fly to Boston to meet my grandfather, but my grandmother had, had never been on an international flight before and was somewhat intimidated.

Harry Yee: I'm Harry Yee I'm Andrew's dad. There was a lot of confusion about where we were supposed to be. And my mother, of course, did not speak any English. And so she glommed on to, uh, a university student, uh, who was at the airport on that flight and went wherever the university student went. That happened to be New York. We were not supposed to fly to New York.

Andrew Yee: When they arrived they were shuttled off to Ellis Island. They really didn't have very many ways to tell my grandfather where they were. So they ended up staying on Ellis island for a few weeks before my grandfather was able to come down and take them back up to Boston.

Harry Yee: I still have dim memories of Ellis island. When we were in the dining hall, I remember, or my, my mother told me, that she used to pass me around to the other Chinese ladies who would carry me up and get milk because that's the only way you would get milk, is if you had a baby. I don't understand why the idiots in the serving line didn't notice that it was the same Chinese kid being passed around seven times for milk.

Yeye finally found us, got us out of Ellis island and, uh, we ended up in Cambridge, Massachusetts. If you didn't work in the restaurant, then you worked in a laundry. There weren't any good choices.

Today laundries or laundromats or dry cleaners, uh, are ordinary sterile places that's not what your typical Chinese laundry looked like.

My parents had a small one and then moved into a larger space and then the larger space they had steam presses in order to press the clothes. In the winter, the steam heat would heat the building. But in the summer it was intolerable. If it was 90 degrees outside and the steam presses are working, it would easily be 110 or 120 degrees inside. You can't air condition a room with a steam press in it. So we had to leave the fans on and the doors open.

That didn't help much at all.

There was no upward mobility. It was a different time and a different place. When I think back about it now it's painful. But I didn't know any better at the time. That was my life. We didn't have much. And they worked hard all the time. The only time that they took off would be, on a Sunday morning to go into Chinatown, to buy groceries and perhaps to go to a Chinese restaurant.

AMBIENCE - Hei La Moon, in Boston

Andrew Yee: My grandparents also brought over other members of the family from China. One of them opened a dim sum restaurant and ran some dim, some restaurants and in Boston, Chinatown for a while. He ran the China, Pearl and Hei La Moon and all of these places that any person who's eaten dim sum in Boston will know and smile about.

My father has a complicated relationship with the Chinese language. He did speak with his parents in Chinese for the rest of their lives. Sometimes would mix in a little bit of English, but, uh, but I remember my whole childhood having him basically as a translator. They did speak English.

My grandmother spoke a little bit more than my grandfather. Um, She was very outgoing and gregarious. And my grandfather was the contemplative one.

Harry Yee: I maintained my Chinese for a while and, uh, but, uh, that has now almost virtually disappeared

Andrew Yee: Not only did he stop using it on a regular basis, but his, um, his dialect is, is basically extinct now. One called Taishan, which was enveloped by Cantonese. So there's not, there aren't very many people in the world who speak it anymore.

Excerpt from American Haiku - pizzicato of main theme

Andrew Yee: What was the experience of, of, of being Chinese for you in Boston during that time?

Harry Yee: It was a different time, there were different norms. It was extraordinarily, well it was impossible for people to immigrate. On a day to day basis, you know, I lived in a kind of rough and tumble neighborhood. I got along with the, the, you know, the people I went to school with, uh, you know, primarily there, it was discrimination. It was more overt then than it is now. You just sort of lived with it. Some of my friends were Black, others were Filipino, and others were Chinese and all of us experienced the world and discrimination in, in kind of different ways and made the best of it. And that's how we live their life. Which is not to say that I had a bad childhood, I had a pretty good childhood I think. You know, I came here not being able to speak English and, uh, you know, I learned English very quickly.

Andrew Yee: So when I would visit my grandparents' house in Cambridge. It was this multi-story sort of townhouse, light blue, and outside were these bushes that were thick with mint plants. So the house had a very specific smell that to this day, every time I smell mint, I, it puts me on, on that porch, sort of the smell of mint and old wood.

My grandfather was a self-taught violinist, and he was very passionate, but he was also very shy knowing that he hadn't been trained. His shelves were lined with recordings of Itzhak Perlman and Isaac stern, and all the great old violinists. And he knew he knew what they were and what he was.

Harry Yee: He, you know, he had a collection of, uh, I guess there were 78s in those days, I mean all, all of the masters of the violin. So, uh, Yeye at his heart, in his heart was, uh, a music appreciator in the best sense of the word.

He was passionate enough that he really wanted to try to make music, uh, to varying degrees of success, but I'm sure it made sense to him and that, he enjoyed it because he continued for as long as I can recall.

Andrew Yee: My memory of sounds that I heard that Yeye was making was more sort of like soundscapes on the violin - did he play songs? What do you recall?

Harry Yee: That's a very kind way of putting it Andrew, uh, soundscapes is, is, uh, is a much kinder way of describing it than I would have described it. Yeye. Uh, while he was dedicated to his violin craft was never actually any good at it and that's not the denigrate Yeye's violin playing. I mean, he derived great enjoyment from it, even if others did not.

Andrew Yee: He never played the violin in the house. He would always take it to a crawlspace underneath the house, which had, it was just dirt. And there were wooden beams and a small lamp and he would go for hours.

Excerpt from In Manus Tuas by Caroline Shaw

The one time that I did see him play the violin, there was when I was, mowing his back yard and going past the crawlspace when he was in there playing, and when I imagine when I imagine him playing is it's that moment in time.

I've been working a lot with the composer, Caroline Shaw, who's one of my very best friends, and I just find myself always coming back to her music and I, I'm not really sure what it is about her music, but there's just something that invites you in and it just sort of changes you on the way out.

And I was thinking about a solo cello piece she wrote called In Manus Tuas. It's about the experience of being in a choir. And hearing the sound of the choir bounce around and the rafters of the cathedral.

And I was thinking about my Yeye, in the crawl space underneath the house and thinking of the beams holding up the house and how beauty is not dictated by a place or a circumstance, music is just music

In Manus Tuas continues

Before he died, I was able to take my cello up to Cambridge. And I remember playing for him a couple of times and just seeing the look on his face when he saw that his grandkid had, had really, really learned the craft. It's a cool thing now to look back on and, and understand how important that moment must have been for him as, as, as a musician to, to see someone who had really done it and, and was doing it on a high level. And I think about him a lot.

End of In Manus Tuas

Parents Meeting, Early Childhood, Learning the Cello

Andrew Yee: My father played a handful of brass instruments growing up, and eventually landed with the baritone. And he met my mother in the marching band at Northeastern in Boston. My mother also played the baritone and one of the, the flirtatious moments they had were my mom had forgotten her mouthpiece and my dad offered her his.

And I love that. And I also love that that's how they met because, because my mother is profoundly hard of hearing and, she must've just really, really loved doing it, you know?

They fell in love and I think about how radical that must have seemed at the time, for a Chinese man and a white woman to walk down the street together and be not only together but happy. It makes me very happy to think of, to think of them as trailblazers in that way.

So after my father graduated from Northeastern. um, he joined the Air Force. And after basic training the sort of question came up who was going to go down the path of learning how to flight planes and who was not. And he decided not to,and, decided instead to have the Air Force, um, pay for his, uh, law school, and he was going to become an attorney in the Air Force. So my family was an Air Force family.

The first place, my family was stationed was in Pennsylvania and then they moved to Florida where my oldest brother David was born, then to Boston, where Ken, my other brother, was born. Then to Rome, New York then to Ohio where I was born, then onto Virginia for a short stint, then to Oklahoma City and then to Germany, and then back to Virginia where my dad retired from the Air Force, and worked at the Library of Congress and that’s where I began to play the cello.

Excerpt from American Haiku by Paul Wiancko

I started playing cello in fourth grade in the public school system. The teacher paused the class and the strings teacher popped in with an arm full of instruments and introduced them to the class. She was a, uh, classically trained violinist and she was not a good cellist and, um, the one thing that she could play, however, was the theme from jaws, that [sings]

And I remember just thinking “that is the absolute, coolest thing I've ever heard.” And she was like, “who wants to play the cello?” And I just raised my hand so hard and I got the forum and I brought it home and I was like, “I really, really, really want to play the cello. And it's so cool. You can play Jaws on it.” My brother Ken at the time, had he played the guitar and he taught me a smashing pumpkin song, “Disarm,” so that was the, that was the second piece I learned on the cello.

The thing about, um, about being in Northern Virginia is that Rostropovich used to conduct the national symphony. So it's a big cello town. It also just made it really fun because there was just a whole, there was a whole lot of good cello-playing and the whole time I was growing up, I was really obsessed with, “oh man, like why, why can that person play the cello like that but I can't?” You know, and, and I would spend all day trying to summon their powers until I had done it.

Excerpt from The Light After by Andrew Yee

I didn't know when I was a kid, you know, what I had and, um. It was just really fun and I always just loved playing the cello for that reason.

I think the turning point for me was when my, uh, elementary school cello teacher, Mary Wagner, said. “All right after, after this year, I can't, I can't teach you anymore.” And originally I thought it was cause I was a bratty kid and she didn't want to deal with me anymore. But, uh, she said, “No, I think you should go study with, with, uh, the man that I studied with,” uh, his name was Lauren D. Stevenson and he was, he was a cellist in the National Symphony. She set up a time when I could go play for him.

He was a hard teacher.

I always felt like a. I was being stacked up against, uh, all these other people. But I got better so quickly, studying with him. And his standards were so high. Um, and that's when I realized. That I had something that, um, that I was good at. And, um, at the time I was a little bit struggling because I had just been diagnosed with ADHD and I was having a hard time sort of, um, sort of staying on task with a lot of things, but cello was always something that I felt like I could, I could put my mind to it and I could accomplish it. And when I did it, people seem to like it, um, which was, um, a really cool thing.

I had a bit of class clown energy when I was younger. And it's really not dissimilar, um, uh, deciding to go into music that you want everybody in the room to just look at you and give you praise for something you just did. And I'm only realizing that now, but I think in, in the early parts of the pandemic, I came to terms with the fact that I wasn't going to walk into a room with hundreds of people clapping for me, uh, anytime soon. And I think I learned a lot about myself in that moment.

For Ashley

Andrew Yee: I first knew that I felt different when I was around eight. It's tough to know, because how well does anyone know themselves when they're that young? There's all sorts of things happening in your head, but, you know, this feeling of every time we played, we played X-Men I wanted to be Rogue, you know, and, uh, every Halloween, which is trans kids’ Christmas, I would, I would, you know, always, um, be some sort of, um, some sort of girl figure or, or a character, cause that was the day that you got to be invisible and visible, at the same time.

I remember my family was late to getting internet. I didn't have internet until, until my teens until I was about 14 or 15. And basically doing– you know this is before a Google, like an Ask Jeeves search of, uh, like what, what am I, you know, what's, what's the deal? Like, why, why do I feel different? The only media that you could find was very sensational. Mostly the place where you could find trans people was on Jerry Springer. And as it was told to all of us as trans kids and trans folk, was the whole purpose of being trans was to fool straight men into sleeping with us. I remember thinking, “but like, I don't want to do that. Like, so I must not be trans,” you know?

Further cementing this idea that trans people were objects, and they were freaks. So it was, um, far too scary to put words to it back then.

I think about it a lot about how. Different my life would have been if I had been able to talk about it, but that was around the time I was, um, diagnosed with ADHD and I already felt like I was kind of a weird kid to begin with. And I didn't really want people to think I was weirder than they already thought I was.

For Ashley by Andrew Norman

When I picked up the music for Andrew Norman's For Ashley I almost I put it back immediately without even looking at the music because, um, it was sort of embedded in the title, uh, this sense of “the piece is for this other person, um, and not you.” And that is not, absolutely not what Andrew meant when he was naming the piece. It was, um, it was either extreme flattery or, or, uh, maybe a little bit of, “I don't feel like coming up with a name for this piece.”

Then I, I looked at the piece and I realized that, that I thought it would be great. Uh, I thought I would sound okay on it. I thought it would, I would have a good time playing it.

And it did, it did remind me of, um, when I first decided to start, um, not using the men's room and feeling like the sign on the wall said, “this is for people who are not you.”

And, um, I remember running in and peeing and running out, not even washing my hands, just from fear of, uh, somebody being mean to me or, or saying something. But it was, um, you know, after a few more times of, of walking into, um, the men's room and just having my, my heart sink, um, I just decided that life was too short and I needed to start, um, just making choices that were, that were good for me.

And so going back to Andrew Norman's piece and I'm, I'm sitting there and I'm holding this music, I'm like, “yeah, I'm going to play this piece because I think it's great.”

My whole project deals a little bit with this feeling of imposter syndrome, where you don't have to be, um, Mixed race or, or trans or non-binary or any of those things to understand imposter syndrome, and that feeling of saying, “Even though I'm uncomfortable, I can belong.”

It is many trans person’s hope, and goal to just be treated as a normal human being. And I didn't think that that was going to be the case if I, if I came out and, I came out when I was 32 to my close friends and I just turned 38 last week.

I have just let it sort of unfurl organically and it, you know, it wouldn't take too much digging to find out, or you could just, you know, look at me.

It always boggles my mind when I walk into a place, you know I have full makeup and wearing like a dress and somebody, “Hello, sir. Can I get, what sandwich can I get for you, sir?” I mean, I, I guess I get it on the phone. I wish the whole sir, and miss, uh, as part of being polite would disappear into the. That would be nice.

I'm not sure if my feeling about how I identify has evolved or how my comfort level has changed over time. And I'm able to really talk about, you know, who I am as a, as a human being and, and whom I've always who I've always been.

MIDROLL

The Sea As It Is

Andrew Yee: Anytime you sort of talk to a group of, of queer folk and they're like, “oh, let's go to the beach,” it's sort of understood that, that you're going to Riis, Jacob Riis. It's a long and sprawling beach. And then the part right at the end in front of a crumbling old hospital is, uh, where all the queer people go. And, it is a place that is sort of sheltered from sight, from the rest of the beach.

Maybe the reason that Jacob Riis has been so important to me is the beach is in most places, is an incredibly gendered place. You know, um, you have, uh, you know, women in bikinis and, and, uh, and the guys wear shorts and that's, that's sort of that. And if you sort of stray from that, um, it's, it's, you know, you get, you get looks. And I think that Jacob Riis allowed me to, to try out some new styles in a place where I felt all right about it. And when I left, I could throw on some shorts and a shirt.

I wrote a piece called The Sea As It Is, which… the piece itself is about the ocean, and about how the ocean can be a place of extreme happiness or sadness. And that doesn't really, um, it doesn't really sort of care.

And then I tell a story of how the beach was the place I had my first date with my fiancé and, uh, and how we keep on coming back to the beach and how that's such a joyful place.

Excerpt from The Sea As It Is by Andrew Yee:

I met the love of my life three years ago. Our first date was at Riis Beach, and if you haven't been, there's a well kept side and there's a side in front of an old abandoned hospital, which is where all the queer folk are.

And that's where we went.

We met on Tinder, and when our plans to go to the beach with our friends both fell through, we decided that we were gonna make that our first date. And we met in front of the library on Cortelyou Road and we rode the bus there together. And it was the first in person conversation we had had.

And at one point our legs touched.

We laughed the entire time and our first kiss was one of those kisses that makes you the hair on the back of your neck stand up. And we tossed in the waves, taking turns, holding each other up.

Last year we went back to Reese to propose to each other,

and last month we took our eight month old for the first time.

And that's why I think we keep finding ourselves at the sea,

‘Cause it's where we come from.

And every time we leave the beach, we know we're gonna find ourselves tumbling back onto the sand like the tide.

Applause (Excerpt from Andrew’s September 16, 2022 performance from the Greence Space)

American Haiku (with Paul Wiancko)

Helga Davis: Our featured artist this evening, Andrew Yee with their piece, The Sea As It Is. So the piece that we’re going to hear is American Haiku, by the composer Paul Wiancko. How does this fit into Halfie?

Andrew Yee: Oh, this piece is about Halfie. You know, having multiple identities, um, Uh, and, and making, making beautiful things out of it. Um, I, I don't see how I could, uh, have a, have a Halfie that didn't have this on it.

Excerpt from American Haiku by Paul Wiancko

Paul Wiancko: My name is Paul Wiancko, and I'm a composer and cellist.

American Haiku, it's a piece that I wrote when I was kind of figuring out my voice as a composer. It was one of my first concert works.

I didn't start writing performance music in earnest until about 10 years ago. So this piece was a bit of an experiment. All of my musical inspirations and fandoms kind of came through in that piece and so it's a bit of a hodgepodge of Jazz and bluegrass and Americana.

Excerpt from American Haiku

When I usually describe it to audiences, I say that it's an identity crisis wrapped in music. I've told that to a lot of people thinking that maybe someday that crisis will be resolved somehow, but that crisis definitely hasn't worked itself out the way I thought it would.

Excerpt from American Haiku

It has brought some things into question and in a way, the style that American Haiku was written in is just my style and I'm realizing that the older I get, and the more music I write, to embrace the crisis of it all.

Andrew Yee: You mentioned a lot of like different musical styles, and even though it has “haiku” in the name, how much of the piece, um, was sort of inspired by, um, by Japan or by Asia or –

Paul Wiancko: Not that much. Not as much as people think. Um, at least ideas, from my conscious brain. Growing up, I listened to a lot of Japanese folk music in my living room, played live by my mom who played koto and was in a koto ensemble. And so that tonality is just kind of. it's in my mind, it's in my ear and I carry it with me and I think it comes out in subtle ways. And that's, I think the role that that’s the role that part of my identity plays in this piece is a very kind of subconscious, um, influence.

There's nothing like this is the Japanese part, you know, it's just, the whole thing is kind of inspired by the kind of succinctness of haiku and the beautiful simplicity um, although the piece isn't necessarily simple structurally, I think the melodic things and the emotion of it is um kind of direct.

Andrew Yee: And, I don't know, I'm curious, your take on it. Cause it sort of took me a while to sort of figure out that I wasn't in touch with my Asian sort of heritage until, until I was, you know, well into adulthood. You know I had always just sort of, I tell people you know I'm half Chinese and, but like, uh, um, I didn't re you know, I sort of didn't you know realize it about myself that I, that I hadn't, I hadn't really been actively, um, engaging with it. Did you, did you sort of have that feeling like as a kid too, or, or how, how does that of resonate with you?

Paul Wiancko: Absolutely. Um, as a half-Japanese person, uh, I had a very similar experience uh, in terms of the timeline of when I wanted to figure that stuff out. it happened much later than you might think. Part of it is just the environment that we are raised in the household and our communities growing up. And, you know, it kind of occurred to me that throughout my upbringing, when I would tell someone, oh, I'm half Japanese, 95% of the time, the first response is like, “what's the other half,” you know, it's not like, “oh, tell me about that experience.” um, which is, you know, that's a natural, of course you want to know, but, um, yeah, uh, it's interesting.

Andrew Yee: Yeah. I still haven't been to China. I feel like I have this block. I have a feeling I'm gonna go to China and then I'm gonna be so embarrassed that I'm not Chinese enough, that I'm just gonna go home.

I'm gonna get there and I'm gonna like have a bowl of soup and then I'm gonna leave... I'm gonna leave a week early.

Paul Wiancko: I mean, that could be a powerful important experience too you know if that's the way goes.

End of American Haiku

The sound of a baby crying in the next room

Otis, Parenthood, and “Oh what a Beautiful Mornin'”

Andrew Yee: As your, as your grandson cries from the other room,

Harry Yee: Uh, yeah, that's Otis

Andrew Yee: that's uh, that’s the life.

Harry Yee: he's up from his nap.

Andrew Yee: Yeah. Aww…

Harry Yee: Focus Andrew.

Andrew Yee: Oh no, I'm just, it'll it'll, the sound of Oatie crying will, will show up and just giving him a second to, uh, I'm giving him a second to sort of calm down.

Harry Yee: Oh, I

Andrew Yee: He normally just is confused when he wakes up and then–

Harry Yee: I thought you were just missing Otis.

Andrew Yee: Oh, I do. I, I miss him so much. I miss him a lot.

All right. Sounds like he's. He's good.

Beat

Andrew Yee: Another thing that I used to Google constantly was, uh, questions about hormone therapy. There were always two red flags that popped up for me. One was the possible loss of libido and one was potential slash likely sterilization.

And in my twenties, I wasn't, I, I wasn't looking to have kids with anyone, you know, but I wasn't, first of all, ready to come out of the closet, let alone start taking hormones. And I wasn't ready to close the door on being able to, to have a kid.

And it wasn't until I met my most recent partner Des that, that I thought, well, you know what? I think that this person, um, I think I want to have a kid with, you know? And, um, she felt the same way, we talked about it.

I had been out for some time and I was still thinking about it, but, um, I decided not to start. And then, um, Des got pregnant. We were trying. And, um, it sort of re-sparked a conversation that I had been having with Des for a while about thinking about hormones and, and you know I was like, “I don't, I don't really know. I don't, I'm not entirely sure.” and basically made the decision to go to the doctor and just sort of talk about it and say like, “Hey, this is something I've been thinking about. Like, what do you think?”

And my doctor was like, “Hey, well, you know, why don't. If you're sort of on the fence about it, you have me now, why don't I just give you a prescription? And, uh, if you want to start taking it, you can. And if not, you can just let it lapse.” And I got, um, patches that they put on your skin that have estrogen. And I have pills that that block testosterone, as well as doing other things, like, you know, like, uh, keeping, uh, my hair looking nice and intact.

So I had them in the cabinet, and Des was in her final two weeks of pregnancy. And I remember just saying to Des, like, “you know, I think, I think it is what I want,” and Des wasn't getting any less pregnant at that point. I went to, you know, the bathroom and I put the patch on and I took a pill and, it ended up being… yeah, about two weeks before my son Otis was born.

And I think two things that that it's cool that we both have this marker around the same time. And I'm really glad that Otis will know that I waited until he showed up and then began this thing that was really important to me. I think that's really cool that he's going to know that, and know that I did that. I'm really happy I waited because he's a really cool kid.

Oh my God. He's the cutest baby. Yeah.

We talked, I talked to Des at length about what our names were going to be. She said I could have whatever I wanted. And we decided that, um, you know, we're, we're both going to be, um, is his moms, he has two moms, um, but Des is going to be his mommy and I am “Ama,” that's A-M-A, then, you know, as he grows up, you know, He'll sort of figure out what, what works for him.

“Oh What a Beautiful Mornin’”

Oklahoma! The musical I was obsessed with when I was, um, three, four years old. Like that was my, uh, Frozen. Yeah, I had a VHS of it and I played it all day long. And, um –

Chorus from “Oh What a Beautiful Mornin’”

That was my jam.

It was a song that I knew really well, which I think is, I'm learning is really important when you're trying to calm down a kid, is that if you know the song really well, you can be doing other things while you're singing that song.

I played the cello from the other day. He heard it happened and he looked startled and looked up and he looked at the cello, then he looked at my hand, they looked up at my face. He was like, “You, you could do this the whole time? And you're singing my songs?” It was really cool to see that realization.

He changes so much every day.

And it sort of stops him in his tracks. You know, if he's having a hard time, um, And, uh, I hold them up against my chest and I sing to him and he can sort of feel my voice through my body. It calms him down immediately,

I really love singing to him.

“Oh What a Beautiful Mornin’”

John Schaefer: This episode was produced by Andrew Yee and Max Fine. Matt Frassica is our editor. Additional production assistance by Jade Jiang, Hanako Yamaguchi, and Laura Boyman. All music performed by Andrew Yee. American Haiku also features violist Ayane Kozasa. Special thanks to Leilehua Lanzilotti, Caroline Shaw, Paul Wiancko, and Concord Music. I’m John Schaefer, thanks for listening.

EASTER EGG

Max Fine: I kind of just heard the close of the whole thing, just listening to that.

Andrew Yee: Yeah, I think this is the one.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.