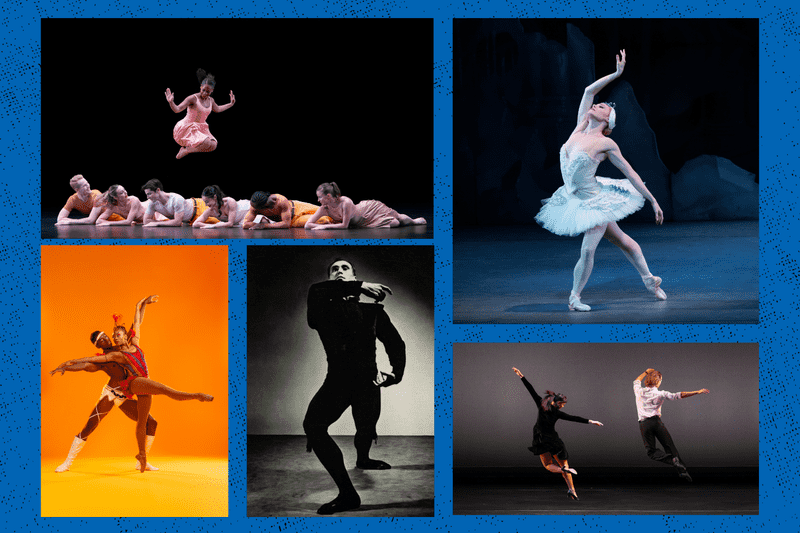

( Whitney Browne, Erin Baiano, Danica Paulos, Walter Strate, Nir Arieli )

Monday: Sara Mearns on Swan Lake

Sara Mearns: I am Sara Mearns and I'm a Principal Dancer within the New York City Ballet. My first New York City ballet experience with Swan Lake is, I was 19, it was my second year in the company and I was chosen to learn Odette/Odile. They picked me out of corps and I started rehearsing it and I debuted the Swan Queen when I was 19. And it was surreal. Honestly, I had already lived so long in this ballet since I was young that it already felt like part of my soul.

For me, the music tells the whole entire story, every single note. Tchaikovsky just really knew what he was doing. The enormity of what he composed, the drama of what he composed, you just feel it so deeply inside you. And also I think what's great is that, when you're doing choreography from Balanchine, who was a genius, you don't have to do more than what he choreographed because for him, music came first. So it's sort of like a perfect package. You know, when you go to watch something like Swan Lake, really try and take in the whole thing, not just the dance, not just the music, but see how it all comes together because there would be no dance without that music.

I have a lot of favorite moments in Swan, but in my head I'm like, every step I take, every movement is leading me to those last moments that I get to experience in this ballet. I can't go with the prince. I have to stay in this world that I was trapped in, that I am now stuck in. I can't become human again. I have to leave him and go back to the swans and we just have to be separated and know that we're both alive, but can never be together. He makes it build and build and build to this crazy, like, dramatic, heartbreaking thing and at the very end, he brings it back down to almost nothing, like literally almost nothing because that's what happens in real relationships. You know, like, the whole, like, fighting and all this “aaaaah” and then at the very end you're just, it's quiet because there's nothing else left to say and all you can do is walk away. And I think that's what really pulls my heart out and I think everybody else too, because you have to live inside of that quiet.

Tuesday: Michael Novak on Esplanade

Michael Novak: I am Michael Novak. I'm the Artistic Director of the Paul Taylor Dance Company. Paul Taylor was born in 1930, and he formed his company in 1954. Dance at that time was asking a lot of questions about like, what is dance? What is art? And when do found sounds, or in Paul's case, found movements and steps actually become art? So there is this whole conversation about simple, everyday movements that we see all the time. And Paul was part of a community of artists that started asking, could this be dance? Could this be something that could be theatricalized and turn into powerful pieces of art? And that started very early in his career but its zenith was in Esplanade, which premiered in ‘75. A lot of choreographers were experimenting with these found movements, but these modern choreographers were doing it to modern music. They would never marry that to preexisting music. Paul Taylor was the first one who really took this modernist approach to movement and married it to baroque music. And it was the two coming together, the old and the new, that shattered the dance world.

It's five different sections. Each has a different mood or a different feeling to it, but all of it is rooted in this idea of simple, everyday movements and gestures. So the fifth section is to the “Violin Concerto in D minor for Two Violins” and it's incredibly fast and virtuosic, but there's something about how Bach creates this sense of anticipation leading into the downbeat. So there's this adrenaline that's building up as you’re hearing it 'cause you're waiting for that note to actually arrive when it does. The other thing that's happening with the two violins is that they're actually exchanging who has the melody or which musical phrase, and it goes back and forth. So you'll have one violin who's just playing this beautiful fast melody, and then underneath that you have this soaring, more expressive or emotional sound, and then it flips. And it's this going back and forth that is incredible to dance to but it's also incredible to hear.

There's a moment where the violins have these chords that they play and it's just this “ba ba ba ba ba ba ba ba ba ba ba” and at that moment that the violins are just sawing away, the women are running, they leap into the air and the men catch them from very far away. You have this anticipation 'cause you have the violins going to town, but then the women are just airborne and you're waiting for them. And then right on that downbeat is when they're caught. So the succession of it mirrors perfectly what Bach is playing as the entire allegro comes to a close. There is something about the marriage of the music and the movement, that audiences can't help but stand up when it's over. It unites people who’ve come to have a theatrical experience.

Wednesday: Mark Morris on The Argument

Mark Morris: I'm Mark Morris and I'm a choreographer. I'm talking about a piece that I choreographed that is Schumann and it's a piece for piano and cello that's called “Fünf Stücke im Volkston.” So it's five pieces in folk style. I originally did this piece because I hadn't ever heard of it, which surprised me 'cause I love Schumann's music. The piece itself was so strange and unlike anything that I know of Schumann's, and it is, it's mysterious and the piece has a certain slyness and a certain distrust in it. I hear some kind of suspicion, like, are we listening to the same thing? Because of how I heard the music, the piece is called The Argument. So The Argument is some kind of a misunderstanding that is happening between three couples. The argument takes place off stage and that they're sort of dealing with it. It's about misunderstanding and making assumptions and as you all know, if you assume something, it makes an idiot out of both of us.

The character of each movement determined for me what kind of problem that couple should be having. So it's like somebody was at a party or they had a fight of some sort and one of them storms out and the other one comes to meet him or her and that's the entrance of the piece as opposed to the exit. Whatever's happening off stage, we don't get to know, but something happened between them and it's uncomfortable.

So the first movement goes “dya dum bum bum ba da dum, bum ba dum dum dee da dum, dyum bum ba da dum.” And it's that catch, “dyum,” it seems sort of scherzando and it's kind of fun and friendly and then it goes “da da da,” which is like, quite sudden and aggressive, at least the way I prefer it to be played. I hear it as sort of semi violent, like, “what are you trying to say to me?” It’s this kind of frustration of a relationship. The dancers have their relationships made up, I dunno what they're doing in the wings, but I know when they enter that it's charged and it's sexy and it's flirtatious. It's a very tense and extremely entertaining dance.

I would say that I choreograph in a way that is represented by the way that music is composed. I find a piece of music that I find puzzling and hear it and study it. The structure, the tone, all of this is what makes the dance happen. So the devices I use are, you know, inversion and canon and retrograde. I do the manipulations of the material, even though it's physical dancing material, it's how composers pull their pieces together and I like that. So that's what I do. So it's not like, here's some music, make up a dance. I can do that. Are you kid- if, if you pay me enough money, I'll make up a dance right here on the spot. Here, wait, I just thought of a dance. Watch this. There. Okay. Now, you at home, you in your car, try it now. All right. So. Cut.

Thursday: Robert Garland on The Firebird

Robert Garland: My name is Robert Garland and I am the third and current Artistic Director for the Dance Theatre of Harlem. Dance Theatre of Harlem was founded in 1969 by Arthur Mitchell, who was the first black male Principal Dancer of a major ballet company. He became a big star at New York City Ballet under the direction of George Balanchine. At one point, Mr. Mitchell went to Mr. Balanchine and said, “Mr. Balanchine, you know, we're getting kind of big here, like, what should I do next?” He said, “you know, I really think that the Firebird you should do for your Dance Theatre of Harlem.”

Most of the productions have leaned into the more Russian design aspect. In our particular production, designed by the brilliant Geoffrey Holder, he set it in Haiti, the lush greenery of Haiti, and, uh, and also added many, many elements of African American design. I, though, personally feel that it is actually kind of afrofuturistic. I often refer to our, our Firebird as a black female superhero who comes and saves the day.

The story itself is about a gentleman that wanders into a forest. He meets a magical bird, and the magical bird, he dances with, becomes kind of infatuated with in our version. And then at one point she needs to leave him. So she leaves and in comes a princess and he immediately becomes smitten with the princess. Then all of a sudden these monsters come destroy everything and take the Princess away from the Prince. And the Firebird comes back, gets rid of all the monsters, and saves the day.

So after the big fight, the Firebird begins to do a dance, and it's a wonderful bourrée solo, meaning, the young lady does all these little tiny runs on the tips of her toes back and forth across the stage. She's accompanied by the Berceuse, which is a lullaby that indeed Mr. Stravinsky knew as a child that he used for this beautifully long solo to have this action go on between the evil villain and the Prince and the Princess, and then to have all that stop and then have a lullaby happen is one of the most amazing things for me to see.

It's a, it’s a remarkable, remarkable piece of music. Built into the Stravinsky score are rhythms and syncopations that he's borrowed from other cultures in many, many different ways. And then adding his own culture that he was raised in, the Russian sound as well, creating something that was new and exciting. It is a wonderful testament to not being stuck only in your own world, but being part of a larger world.

Friday: Logan Frances Kruger on Chaconne

Logan Frances Kruger: My name is Logan Frances Kruger, and I am the Associate Artistic Director of the Limón Dance Company. José Limón was born in Culiacán, Mexico in 1908 and he moved here with his family, immigrated to the United States, and quickly became one of the most well-known dancers of his time. And then became a choreographer and started this company, which is entering its 80th anniversary this year.

Limón made this solo for himself in 1942 which is danced to Bach's “Partita in D Minor, The Chaconne.” He lived at the time in an apartment on 13th Street, and he talks about moving the chairs and the tables to the sides of the apartment, and he would set the phonograph and listen, and listen, and listen and listen. He was really trying to capture the structure and the sense and the feeling of that piece of music. He also said before he ever started choreographing to it, that he had lived with that piece of music for a long time.

While it's completely abstract and really is about the music, when you watch it on stage you see the journey of this individual. They start in the corner, and they just kind of keep making their way down the diagonal, keep coming back and around, keep coming back and around, keep coming back and around, and eventually they open up the space. And finally, about three quarters of the way through the solo, they've fully entered and owned the entirety of this stage. I see a lot of, nobility of spirit and a lot of perseverance in this solo. So much of the work and Limón's choreography deals with humanity and the human condition and what it is to exist on this planet, being pulled down by gravity and getting up every day and the resiliency of our spirit.

What must it have been like for a Mexican immigrant to move here, to learn to speak another language, to have to speak it well enough to be accepted, making his way as a brown man in a very white world in that time in our country? I can't not see that when I think about him making this solo in 1942.

When you combine the craft of choreography with this beautiful music, and with the vulnerability of the performers to take that kind of risk and put yourself out there and stand and be revealed for who you are, it's so beautiful and it's so moving. And I think, you don't have to know anything about dance or anything about music to see that, to hear that, to witness that, and see yourself, somehow, in what's happening on stage.

Copyright © 2025 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.